UDK: 616.833-089.5:534.321.9

Kraleva S1, Trojikj T1,2, Bozinovska Beaka G2,3, Shirgoska B4, Malinovska-Nikolovska L5

1Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care, City General Hospital “8th of September”, Skopje

2Faculty of Medical Sciences, “Goce Delchev” University, Shtip, North Macedonia

3Department of Abdominal Surgery, City General Hospital “8th of September”, Skopje

4Department of Anesthesiology, ENT University Clinic, Skopje

5Department of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Acibademsistina Clinical Hospital, Skopje

Abstract

Introduction: Peripheral nerve blocks have an increasingly important role as an anesthetic technique for surgical anesthesia, postoperative analgesia, and fast discharge of patients after surgery involving the upper or lower extremities, alone or in combination with spinal or general anesthesia. Ultrasound guidance has become the most popular for performance of peripheral nerve blocks.

Methods: In our retrospective study, we included all patients that were admitted in our hospital for orthopedic procedures on lower and upper extremities who received peripheral nerve block, alone or in combination with spinal or general anesthesia in the last 5 years. Ultrasound guidance was used and local anesthetic Bupivacaine 0.5%. Dexamethasone 4 mg was given intravenously as an adjuvant to peripheral nerve blocks.

Results: The total number of patients included in our study was 300, the total number of performed peripheral nerve blocks was 302. 144 (48%) patients were male and 156 (52%) – female. The type of performed blocks was: 164 (54%) femoral, adductor canal blocks 22 (7.28%), 26 supraclavicular (8.60%), 77 interscalene (25.49%), 9 axillar (2.98%), 2 popliteal (0.66%), 1 iPACK and 1 TAP block (0.33%). Peripheral nerve blocks were combined with general or spinal anesthesia or performed as a sole technique for intraoperative analgesia in 17 patients (5.67%).

Discussion: In our hospital we performed ultrasound guided peripheral nerve blocks last years in combination with a general, spinal anesthesia or as a sole technic for intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. Our patients were very satisfied with good postoperative pain control, and no serious complications were observed.

Conclusion: Ultrasound guided peripheral nerve blocks are good choice for intraoperative anesthesia and postoperative analgesia, especially in older patients and patients with a lot of comorbidities.

Key Words: orthopedic surgery; peripheral nerve blocks; ultrasound guidance

Introduction

Regional anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks have an increasingly important role as an ideal anesthetic technique for surgical anesthesia, prolonged postoperative analgesia and facilitated discharge of patients after surgery. Peripheral nerve blocks can be used to provide regional anesthesia for operations involving the upper or lower extremities (1).

Peripheral nerve blocks have been part of anesthetic techniques used for upper extremity surgery for decades. The interscalene block was described a century ago, in the early 1900s. These blocks at the beginning were done by identifying anatomical landmarks and eliciting paresthesia. The introduction of the nerve stimulator technique in the late 1980s made a change in practice, but introduction of the ultrasound technique during the last decade has further enhanced the performance. A Cochrane review suggests that the ultrasound-guided block technique further improves the success and ease of performance, and it is now commonly used by younger colleagues (2). It offers a lot of practical advantages for nerve blocks, good visualization of the anatomy, more informed guidance for the needle pathway to the nerve while avoiding structures that might be damaged by the needle (3). Ultrasound guidance reduces the block performance time, the number of needle passes and shortens the block onset time using lower LA doses (4). Significant impact is reduction in block-related complications, nerve injury, intraneural injection of anesthetic, reduced incidence of systemic local anesthetic toxicity, intravascular injection, direct visualization of non-neural structures, e.g., pleura and kidney.

Peripheral nerve blocks provide surgical anesthesia and minimize the need for general anesthesia, opioid requirements are reduced, as are opioid-related side effects. Peripheral nerve blocks with long-acting local anesthetic can provide prolonged analgesia (5).

Regional anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks improve the cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, coagulative, immunological and cognitive functions, especially for elderly and high-risk patient populations undergoing surgery (6).

Peripheral nerve blocks can be used alone or in combination with general anesthesia for intraoperative analgesia. It depends on the site of surgery, refusal or acceptance of the patient. The depth of GA is reduced and the use of intraoperative opioids minimized, so we have early return of cognitive function (7). Especially, upper extremity nerve blocks of plexus brachialis have an obvious place as a sole anesthetic technique or as a powerful complement to general anesthesia.2 A failed peripheral nerve block is associated with patient’s discomfort and unnecessary conversion to general anesthesia. The reported success rate of ultrasound-guided blocks ranges from 55% to 100% (8).

Some additives to local anesthetics can hasten the onset of nerve block, prolong block duration or reduce toxicity. Recent studies suggest that giving additives intravenously or intramuscularly can provide the same benefits of perineural administration while reducing the potential for neurotoxicity. Dexamethasone is the most popular additive, and it can be used perineural or intravenously with the same prolongation of the blocks. Dexamethasone reduces postoperative opioid consumption, has an important effect in reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting (9).

Methods

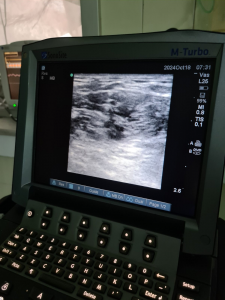

In our study, we included all patients, ASA 1-3, that were admitted to our hospital for orthopedic procedures on lower and upper extremities who received peripheral nerve block, alone or in combination with spinal or general anesthesia in the last 5 years. Peripheral nerve blocks were performed following protocols for patients’ safety. The nerve blocks were performed usually 15 to 30 minutes before the surgery. Ultrasound guidance with a 6–13MHz linear ultrasound probe (M-Turbo, SonoSite ultrasound) (Picture 1) and Stimuplex needle by B/Braun were used.

Picture 1. SonoSite Ultrasound.

The procedure was explained to all patients. They were monitored with standard monitoring (EKG, sPO2, BP) and i.v. canula was inserted with an infusion of 0.9% Saline. Bupivacaine 0.5% was used in dose depending on the type of peripheral nerve block and the patient. We did not use perineural dexamethasone or any adjuvant to local anesthetic, we used dexamethasone 4mg intravenously.

In the operation room, our patients received general or spinal anesthesia, or in some cases peripheral nerve block was a sole technique for intraoperative anesthesia. All patients during surgery received famotidine 20mg, metoclopramide 10mg, paracetamol 1gr and ketoprofen 160mg. Spinal anesthesia was performed after putting the patient in a sitting position, using Bupivacaine 0.5% in a dose depending on the type of surgery and the patient, in combination with fentanyl 0.2ml. Introduction in general anesthesia was with midazolam, fentanyl, propofol and rocuronium. After intubation, general anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane. The dose of fentanyl used intraoperatively was reduced, because general anesthesia was combined with nerve blocks of plexus brachialis.

During surgery for upper extremities, especially for shoulder procedures in the sitting position we used NIRS monitor, cerebral oximetry on both cerebral hemispheres (Picture 2).

Picture 2. Sitting position and NIRS monitor.

Results

The total number of patients that were included in our study was 300. They were admitted to our hospital for elective orthopedic surgery, or with fractures for emergency surgery. The total number of performed peripheral nerve blocks was 302.

Table 1. Gender of population.

| Gender | Total | |

| Male | Number | 144 |

| % | 48% | |

| Female | Number | 156 |

| % | 52% | |

| Total | Number | 300 |

| % | 100% | |

Table 1 shows gender of included patients: 144 (48%) patients were male and 156 (52%) – female.

Table 2. Type of performed blocks.

| Type of peripheral nerve block | Number | % |

| Femoral | 164 | 54.3% |

| Adductor canal block | 22 | 7.28% |

| Supraclavicular | 26 | 8.61% |

| Interscalene | 77 | 25.5% |

| Axillar | 9 | 2.98% |

| Popliteal | 2 | 0.66% |

| iPACK | 1 | 0.33% |

| TAP | 1 | 0.33% |

| Total | 302 | 100% |

Table 2 shows the type of performed blocks: 164 (54%) femoral blocks, 22 adductor canal blocks (7.28%), 26 supraclavicular blocks (8.60%), 77 interscalene blocks (25.49%), 9 axillar blocks (2.98%), 2 popliteal blocks (0.66%), 1 iPACK and 1 TAP block (0.33%). One patient received both interscalene and axillary block, and one patient received femoral plus iPACK block. Peripheral nerve blocks performed for surgery on lower extremities were combined with general or spinal anesthesia, but blocks for upper extremities were combined with general anesthesia or performed as a sole technique for intraoperative analgesia in 17 patients (5.67%). The youngest patient who was operated only with peripheral nerve block was 17 years old, and the oldest was 78 years old.

The average duration of analgesia after peripheral nerve blocks in our patients was 20.5 hours.

Discussion

Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia has become very popular in recent years. The use of ultrasound optimizes the technique of peripheral nerve blocks and reduces the dose of local anesthetic used (10). A Cochrane review suggests that the ultrasound-guided block technique improves the success and ease of performance (11). This re-review supports the efficacy of the ultrasound-guided block technique but also addresses the importance of experience and the training curve of ultrasound vs. other techniques. Neal et al.concluded that there is high-level evidence supporting ultrasound guidance, contributing to superior characteristics with selected blocks (12).

In our hospital, we performed ultrasound guided peripheral nerve blocks last years in combination with general anesthesia, spinal anesthesia or as a sole technique for intraoperative and postoperative analgesia. In cases for lower extremity surgery peripheral nerve blocks were combined with spinal or general anesthesia, but for upper extremity surgery peripheral nerve blocks were used alone or in combination with general anesthesia.

After surgery in spinal anesthesia, all patients spent 5-10 minutes in the recovery room, and were sent to the surgical ward in a stable condition. Patients operated under general anesthesia in combination with nerve block were awakened and extubated in the operation room, and after 15 minutes spent in the recovery room, they were sent to the surgical ward in a stable condition. Consumption of opioids during the general anesthesia was minimized, as we expected, with an early recovery of the cognitive function. The postoperative pain in both groups (GA or SA) was reduced in the first hours postoperatively.

On the occasion of lower extremity surgery, femoral nerve block was performed in most of the cases, 164 (54%), admitted for knee and hip surgery. No complications or adverse events were detected. Postoperative pain and the need for additional analgesics were reduced in the first 24 hours postoperatively. A recent systematic review limited to English language publications up to 2009 concluded that single‐shot or continuous femoral nerve block was superior to PCA or opioid alone for acute pain control in the first 72 hours after knee replacement. Also, they found that single‐shot FNB leads to lower pain scores during movement at 24 hours and at 48 hours; lowers opioid requirement at 24 hours and at 48 hours and lowers risk of nausea and vomiting (13). In our cases, no rebound pain was observed, and all patients were verticalized next day.

Adductor canal block was performed in 22 cases (7.28%), in patients admitted for knee arthroplasty or ligamentoplasty. No complications or adverse events were detected.

Popliteal nerve block was performed only in 2 patients, admitted for surgery of Hallux valgus, combined with spinal anesthesia. The next day both were discharged home with no complaint of pain and very satisfied.

The upper extremity blocks we used in our practice were interscalene, supraclavicular and axillar nerve block. The total number of patients who received these blocks was 112 (37.07%). Most of the patients were admitted for elective surgery, but some of them were admitted with fractures of upper extremity.

Upper extremity plexus blocks have an obvious place as a sole anesthetic technique or as a powerful complement to general anesthesia, reducing the need for analgesics and hypnotics intraoperatively, and provide effective postoperative pain relief (2). 17 (5.66%) patients for upper limb surgery were operated only with nerve block of plexus brachialis. In other cases, the plexus brachialis nerve blocks were combined with general anesthesia. During general anesthesia, only 2ml of fentanyl was given in the beginning for induction. Intraoperatively we did not use more opioids because analgesia with the peripheral nerve block was enough. Because of a small dose of opioids, our patients were awakened from general anesthesia very quickly and with no complaint of pain. Postoperative analgesia with nerve blocks was excellent and the need for additional analgesics was reduced in the first 24 hours.

The upper extremity blocks with their motor and sensor components, especially interscalene blocks have the same meaning as a spinal anesthesia for lower extremity surgery. Ultrasound guidance was used, single shot performed with a long-lasting local anesthetic bupivacaine 0.5%. The blocks were successful at the first attempt. No serious complications, regarding to intravenous application, nerve damage, local anesthetic toxicity, pneumothorax or Horner’s syndrome were observed. In two young male patients, transient difficulty with breathing (mild shortness of breath) was observed after interscalene block, but after 30-40 minutes it disappeared. Some studies reported a high incidence of Horner’s syndrome. Tran et al. compared ultrasound-guided supraclavicular, infraclavicular and axillary brachial plexus blocks for upper extremity surgery of the elbow, forearm, wrist and hand (14). They found all three blocks to be effective; however, the axillary block required longer time to perform, and the supraclavicular block was associated with a higher incidence of Horner’s syndrome. Gamo K et al. examined the outcomes and levels of patients’ satisfaction in 202 consecutive cases of ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block (SBPB) in upper limb surgery and found that a total of 20 patients (10%) developed a transient Horner’s syndrome (15). No nerve injury, pneumothorax, arterial puncture or systemic anesthetic toxicity were recorded. Vaghadia H et al.compared ropivacaine 0.75% versus bupivacaine 0.5% for supraclavicular brachial plexus anesthesia (16). After informed consent, 104 ASA I–III adults participated in a randomized, double-blind, multi-center trial to receive 30ml of either ropivacaine 0.75% or bupivacaine 0.5% for subclavian perivascular brachial plexus block prior to upper limb surgery. Onset and duration of sensory and motor block in the distribution of the axillary, median, musculocutaneous, radial and ulnar nerves were assessed. Onset times and duration of sensory and motor block were similar between groups. The mean duration of analgesia for the five nerves was between 11.3 and 14.3 hours with ropivacaine, and between 10.3 and 17.1 hours with bupivacaine. The quality of muscle relaxation judged as excellent by the investigators was not significantly different. The median time to the first request for analgesia was comparable between the two groups (11–12 hours). In our cases muscle relaxation was excellent, the shortest duration of analgesia was 13 hours, and longest duration was 30 hours in a male patient. In our practice we did not use dexamethasone or epinephrine in combination with local anesthetics. We used dexamethasone 4mg given intravenously at the beginning of the surgery. In one study dexamethasone was observed to increase median block duration by 37% (95% confidence interval: 31-43%). Dexamethasone was also observed to reduce pain scores on the day of surgery (P=0.001) and postoperative day 1 (P<0.001). There was no significant difference in duration of nerve blocks when epinephrine (1:400,000) was added to ropivacaine with or without dexamethasone (17).

Srikumaran U et al. concluded that peripheral nerve blocks for upper-extremity procedures improve postoperative pain control and patients’ satisfaction, can be administered safely, and have a low complication rate. They are also associated with enhanced participation in postoperative rehabilitation, decreased hospital stays and decreased costs. For our patients who received peripheral nerve block for intraoperative anesthesia and postoperative analgesia, we concluded the same (18). Our patients were very satisfied with good postoperative pain control, and no serious complications were observed. The most of them were discharged home the next day after surgery in a good condition and very satisfied. No rebound pain and readmissions were detected.

Conclusion

Ultrasound guided peripheral nerve blocks are a good choice for intraoperative anesthesia and postoperative analgesia, especially in older patients and patients with a lot of comorbidities. Peripheral nerve blocks give us better intraoperative stability of patients, fast awakening from general anesthesia and very satisfied patients with no pain after surgery.

References:

- Joshi G, Ghandi K, Shah N, et al. Peripheral nerve blocks in the management of postoperative pain: challenges and opportunities. J Clin Anesthesia 2016; 35: 524–529.

- Brattwall M, Jildenstål P, Warrén Stomberg M, Jakobsson JG. Upper extremity nerve block: how can benefit, duration, and safety be improved? An update. F1000Res. 2016 May 18;5:F1000 Faculty Rev-907. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7292.1. PMID: 27239291; PMCID: PMC4874442.

- Orebaugh SL, Kirkham KR. Introduction to Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia. Nysora. 2023.

- Koscielniak‐Nielsen ZJ. Ultrasound‐guided peripheral nerve blocks: what are the benefits. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2008 Jul;52(6):727-37.

- Klein SM, Evans H, Nielsen KC, et al. Peripheral nerve block techniques for ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005 Dec;101(6):1663-1676. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000184187.02887.24. PMID: 16301239.

- Nielsen KC, Steele SM. Outcome after regional anaesthesia in the ambulatory setting–is it really worth it? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002 Jun;16(2):145-57. doi: 10.1053/bean.2002.0244. PMID: 12491549.

- Capek A, Dolan J. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve blocks of the upper limb, BJA Education, Volume 15, Issue 3, June 2015, Pages 160–165.

- Marhofer P, Sitzwohl C, Greher M, Kapral S. Ultrasound guidance for infraclavicular brachial plexus anaesthesia in children. Anaesthesia 2004; 59:642–6.

- Huynh TM, Marret E, Bonnet F: Combination of dexamethasone and local anaesthetic solution in peripheral nerve blocks: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015; 32(11):751–8.

- Nowakowski P, Bieryło A, Duniec L, et al. The substantial impact of ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia on the clinical practice of peripheral nerve blocks. Anaesthesiology Intensive Therapy. 2013; 45(4):223-9.

- Lewis SR, Price A, Walker KJ, et al. Ultrasound guidance for upper and lower limb blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 9: CD006459. 10.1002/14651858.CD006459.pub3.

- Neal JM, Brull R, Horn JL, et al.: The Second American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Medicine Assessment of Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia: Executive Summary. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(2):181–94. 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000331).

- Paul JE, Arya A, Hurlburt L, et al. Femoral nerve block improves analgesia outcomes after total knee arthroplasty: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology 2010;113(5):1144‐62.

- Tran DQ, Russo G, Muñoz L, et al.: A prospective, randomized comparison between ultrasound-guided supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary brachial plexus blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34(4):366–71. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181ac7d18.

- Gamo K, Kuriyama K, Higuchi H, et al. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block in upper limb surgery. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(6):795-799. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B6.31893.

- Vaghadia H, Chan V, Ganapathy S, et al. A multicentre trial of ropivacaine 7.5 mg• ml− 1 vs bupivacaine 5 mg• ml− 1 for supraclavicular brachial plexus anesthesia. Canadian journal of anesthesia. 1999 Oct; 46:946-51.

- Rasmussen SB, Saied NN, Bowens C Jr, et al. Duration of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve blockade is prolonged with dexamethasone when added to ropivacaine: a retrospective database analysis. Pain Med. 2013 Aug;14(8):1239-47. doi: 10.1111/pme.12150. Epub 2013 Jun 11. PMID: 23755801.

- Srikumaran U, Stein BE, Tan EW, et al. Upper-extremity peripheral nerve blocks in the perioperative pain management of orthopedic patients: AAOS exhibit selection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013 Dec 18;95(24):e197(1-13). doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01745. PMID: 24352782.