UDK: 616.833.34-089.5:616.717.4-001.5-089.168-009.7

Temelkovska Stevanovska M1, Dimitrovski A1, Panovska Petruseva A1,2, Gavrilovska Brzanov A1,2

1University Clinic for Traumatology, Orthopedic, Anesthesia, Reanimation and Intensive Care and Emergency Center, Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia

2 University „Ss. Cyril and Methodius”, Faculty of Medicine. Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia

Abstract

Introduction: We can use the supraclavicular block as a postoperative pain management approach, as an addition to general anesthesia, or as the sole form of anesthesia for upper limb surgery. For upper limb surgery, this block is a fantastic substitute for general anesthesia in patients with pulmonary and cardiac comorbidities.

Case Presentation: In order to undergo surgery for a fracture of the proximal portion of his upper arm, a 66-years-old male AA was brought to the Clinic for Orthopedic Diseases in Skopje. The anesthesiologic examination revealed that the patient had diabetes mellitus type II, cardiomyopathy, untreated ischemic heart disease and wheezing and crepitations in the distal portions of his lungs. We planned the open fixation of the fracture for the patient. A supraclavicular brachial plexus block was performed as the most non-invasive procedure for perioperative treatment, taking into consideration the patient’s health. The patient’s vital indicators were normal and stable during the procedure. After receiving therapy for two days, the postoperative course was uneventful, leading to the patient’s discharge.

Conclusion: If not addressed earlier, preoperative pulmonary and cardiac comorbidity increases the risk of perioperative and postoperative problems. With no postoperative problems, peripheral nerve block – in our case, supraclavicular brachial plexus block – proved to be a safe option for anesthesia management used for upper limb surgery.

Key Words: anesthesia Brachial plexus block; fracture of upper arm; postoperative complications; supraclavicular block.

Introduction

Patients with pre-existing pulmonary and cardiac conditions have an increased risk for perioperative complications and an increased mortality rate (1). High-risk pulmonary patients, in particular, who undergo general anesthesia may be more prone to risks of barotrauma, postoperative hypoxemia, pneumonia and respiratory failure after surgery (1,16). Patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions are also at risk for experiencing perioperative complications and increased morbidity (1). High cardiac risk patients are those with previously diagnosed coronary artery disease – CAD (as indicated by previous myocardial infarction, typical angina, atypical angina with positive stress test results or angiography), or were at high risk for CAD stratified according to ACC/AHA – American College of Cardiology /American Heart Association criteria (2).

The functional capacity examination covers the estimated energy requirement for various activities. It is defined as MET = metabolic equivalent, which is measure for heart metabolic demand during different daily activates, shown in Table 1 (3).

Table 1. Functional capacity.

| 1 МЕТ | Self-care? |

| Eating, dressing, or using the toilet? | |

| Walking indoors and around the house? | |

| Walking one to two blocks on level ground at 2 to 3 mph? | |

| 4 METs | Light housework (e.g., dusting, washing dishes)? |

| Climbing a flight of stairs or walking up a hill? | |

| Walking on level ground at 4 mph? | |

| Running a short distance? | |

| Heavy housework (e.g., scrubbing floors, moving heavy furniture)? | |

| Moderate recreational activities (e.g., golf, dancing, doubles tennis, throwing a baseball or football)? | |

| >10 METs | Strenuous sports (e.g., swimming, singles tennis, football, basketball, skiing)? |

| MET – metabolic equivalent; mph = miles per hour | |

The persons with major predictors and 1- 3 МЕТ-s have high postoperative cardiac risk while these with МЕТ≥ 4 have low postoperative cardiac risk (3).

General anesthesia is traditionally used for upper extremity surgery. Perioperative complications can be minimized with careful management.

However, regional techniques are increasingly being used as stand-alone anesthesia techniques, as an adjunct to general anesthesia, or for the treatment and control of postoperative pain (5,6). The traditional regional anesthesia techniques for shoulder surgery are associated with high rates of phrenic nerve paralysis which significantly impairs pulmonary function (7). Newer regional anesthesia techniques, such as using ultrasound visualization with a high-frequency linear probe and lower amount of local anesthetic, provide effective analgesia and surgical anesthesia while having much lower rates of phrenic nerve paralysis, thereby preserving pulmonary function (8-11).

The brachial plexus is formed by ventral (anterior) rami of nerve roots C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1. As these roots course distally, they rearrange to form trunks, divisions, cords and lastly branches. The supraclavicular approach to blocking the brachial plexus is thought to occur at the level of the nerve trunks. The brachial plexus is the most compact at the level of the trunks and so injecting local anesthetics here gives the greatest likelihood of blocking all the branches of the brachial plexus (8,9).

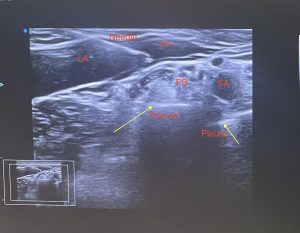

The ultrasound probe is placed in the supraclavicular fossa in the transverse orientation parallel to the clavicle, and behind the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and aimed inferior toward the ipsilateral thorax. The brachial plexus and the subclavian artery are visualized (Picture 1). The first rib appears as a hyper echoic line with the lung pleura deeper to this bony border. Utilizing the in-plane approach, the needle is advanced from lateral to medial, aimed for near the main neural cluster of the brachial plexus. After negative aspiration, local anesthetic (about 10mL) is injected (Picture 2). Subsequently, smaller aliquots of local anesthetic are deposited near the surrounding satellite neural clusters (8). Injection should be stopped if the patient experiences paresthesia or pain.

BP-Brachial plexus; BP-Brachial plexus;

SA- Subclavian artery SA- Subclavian artery

LA-local anesthetic

Picture 1. Picture 2.

Another approach is “the corner pocket technique,” first described by Soares and colleagues in 2007 (9). This involves a needle trajectory aimed towards the deeper portion of the brachial plexus with the goal of local anesthetic solution raising the brachial plexus off from the first rib. Then, the needle is retracted and advanced at a shallower angle, aiming towards the superficial brachial plexus. After negative aspiration, a local anesthetic is injected (about 10 mL) (9). This technique may have higher potential for pleural puncture.

The neurostimulator can be used as an additional technique to the ultrasound (10). When using a direct current of 0.5mA, contraction of the corresponding muscles of the arm occurs. By reducing the current to 0.3mA, the contractions stop, which indicates that the needle is far enough from the nerve plexus and the local anesthetic can be safely applied without risking nerve damage. Neurostimulator provides additional safety when performing the block using ultrasound and reduces the risk of intraneural application of local anesthetic (10).

Complications that occur when performing supraclavicular block include the risk of infection, hematoma, neuropathy and systemic toxicity when intravascular application of local anesthetic happened (10). Other complications may include hoarseness due to ipsilateral laryngeal nerve block, Horner’s syndrome due to stellate ganglion block, and hemi diaphragmatic paresis due to phrenic nerve block. However, with ultrasound-assisted supraclavicular block, these complications are very rare (7,10-12).

Contraindications for supraclavicular block include patient’s refusal, allergy to local anesthetic, infection at the puncture site, neurological deficit and coagulopathy (10,13).

Despite the possible side effects, supraclavicular brachial plexus block has been shown to be a safe choice over general anesthesia in patients with pulmonary and cardiac comorbidities, providing excellent 24-hours postoperative analgesia, shorter hospital stays and significant patient’s satisfaction with this type of anesthesia (14-26).

Case Report

A 66-years-old male AA (height 180cm, weight 110kg) was admitted to the Clinic for Orthopedic Diseases in Skopje for surgical treatment of a fracture of the proximal part of the upper limb. The initial assessment upon admission revealed respiratory status with wheezing and crepitation in the basal parts of the lungs, but without recent coughing episodes, absence of dyspnea, and no edema. Chest X-ray was with signs of congestive changes, aggravated bronchovascular pattern and enlarged cardio-thoracic (CT) ratio. SpO2 – 95%. The patient reported being a smoker, 30 cigarettes per day. The ECG showed a widened QRS segment, supraventricular tachyarrhythmia and pronounced depression of the ST segment. Complete laboratory analysis and hemostasis were without significant changes except for elevated values of glycaemia, total lipids and cholesterol. The patient did not provide information about any health problems, claiming that he felt completely well, but functional capacity examination revealed that he felt tired when climbing stairs and uphill and did not practice walking for long distances at all. He did not engage in heavy physical work. He was a professional driver. There were no results from previous cardiological, pulmonary and general internal medical tests, nor any information about previous surgical interventions. He only was taking regular oral therapy for hypertension (calcium channel blocker), statins and diabetes. He was classified as ASA III status. Preoperatively, he was referred to the cardiologist, and he was put on oral bisoprolol (beta blocker) 5mg once daily.

After 2 days, the patient was scheduled for an open fixation of the upper arm fracture. The choice for perioperative management was to perform a supraclavicular brachial plexus block, as the most non-invasive technique, taking into account the patient’s health condition.

After explaining the technique of performing the block, the feeling of arm numbness for a longer period of 16-20 hours and the risks associated with supraclavicular block and the growing evidence about the safety of this form of anesthesia in relation to the underlying condition, the patient accepted the technique and signed the informed consent.

The supraclavicular block was performed 30 minutes before the start of the surgical intervention, at the recovery room. Basic monitoring, ECG, non-invasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry was set up and he was sedated with iv. diazepam 5mg. The block was performed using ultrasound and a neurostimulator at the same time. After ultrasound identification of the plexus (Figure 1), with an 50mm, 18 G neurostimulator needle and an “in plane” lateral-to-medial approach technique in which the entire length of the needle is followed, local anesthetic 0.5% bupivacaine 20ml, 2% lidocaine 9ml and dexasone 4mg was applied by aspiration of every 5ml. 20ml in the upper part of the plexus (Figure 2) and 10ml in the lateral and distal parts. The patient’s hand began to become numb after a few minutes and complete numbness and inability to lift it occurred after 15 minutes.

Preoperatively, basic monitoring was set such as ECG, non-invasive blood pressure and pulse oximetry. Initial parameters were: NIBP 150/90mmHg, HR 75b/min and SpO2 96%. The patient was managed on an oxygen mask with a flow rate of 4L/min and 1500ml saline 0.9%. The surgical intervention lasted 2 hours and the patient was stable throughout the entire period with normal vital parameters. ECG was monitored at 12 drains and during the intervention there was no worsening of the already existing ST depression, nor any other changes compared to the previously diagnosed ones. During the surgical intervention the patient did not feel pain and did not need additional sedation besides diazepam which was given before the block performance. The block lasted 18 hours and after its discharge the patient had a normal motor and sensory status of his upper limb.

In the postoperative period the patient was treated with antibiotics and anticoagulant therapy. Pain relief drugs were given after 24 hours, such as acetaminophen and NSAIDS. He was discharged from the surgical clinic after 2 days in good general condition with the same previously established cardiac and respiratory changes and advised undergo complete analyses in order to obtain appropriate cardiac and health treatment.

Discussion

Peripheral nerve blocks are routinely performed in our institution for upper limb surgery. In the referred case, the patient’s cardiac and pulmonary findings were an additional reason for performing a regional technique in order to provide better perioperative stability and satisfactory analgesia, without the use of opioid and non-opioid analgesics. The patient had stable vital parameters during the surgical intervention and was discharged after 2 days in good general condition.

The decision to use regional anesthesia can be a complex medical choice. Preexisting medical conditions, type of surgery, anesthetic risks, and patient’s characteristics all may have a profound impact on anesthetic choice and perioperative management. In patients with cardiovascular disease, regional anesthesia techniques (either alone or in conjunction with general anesthesia) can offer the potential perioperative benefits of stress response attenuation, cardiac sympathectomy, earlier extubating, shorter hospital stay and intense postoperative analgesia (10).

Lee et al. investigated the use of peripheral nerve blocks for orthopedic shoulder surgery in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These patients, under general anesthesia, may develop respiratory failure and require mechanical ventilation in the postoperative period, which further increases the risk of postoperative morbidity and mortality. The authors examined several combinations of regional anesthesia, including a supraclavicular block – the application of local anesthetic in the area of the upper pole of the plexus where the upper trunk is localized. In addition to the regional anesthetic technique, the volume of local anesthetic is an important factor that may influence the risk of potential Horner’s syndrome or even hemi-diaphragmatic paresis. A certain minimum dose of local anesthetic is necessary to provide either surgical anesthesia or analgesia. For example, the superior trunk block has demonstrated efficacy using 15mL of bupivacaine 0.5% and 20mL of levobupivacaine 0.5%, respectively. By limiting the volume of local anesthetic, the risk of proximal spread of local anesthetic to the phrenic nerve and resulting diaphragmatic paresis is reduced. With newer techniques and greater clinician experience, regional anesthesia may offer important benefits for patients undergoing shoulder surgery while minimizing the side effects associated with this technique (16).

Ozen in his case report study used ultrasound guided selective supraclavicular nerve and low-dose interscalene brachial plexus block in a 67-years-old patient with coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) who was scheduled for open fixation of the fracture of his right clavicle. The supraclavicular block was performed with 4ml of bupivacaine 0.5%, in order to provide intra- and postoperative analgesia in the area around the acromioclavicular joint. To provide a block of the interscalene plexus, 10ml of bupivacaine 0.5% were applied. With this dose of local anesthetic, complete motor and sensory block was achieved. Surgery was performed without any hemodynamic instability or complications. According to this study, low dose peripheral nerve block is an alternative option at high-risk patients due to heart and lung disease (17).

Kim et al., and Mardirosoff and Dumont in their studies refer to possible complications of semi diaphragmatic paresis and convulsions associated with the large amount of anesthetic administered during interscalene block (11,12). In the study by Kim et al., interscalene block was performed as an adjunct to general anesthesia to achieve postoperative analgesia and it is recommended to compare a dose of 5ml versus a dose of 15ml. The conclusion of this study is that a 5ml dose of local anesthetic provides the same analgesia as a 15ml dose (11). In the study by Mardirosoff and Dumont, convulsions appeared because 80ml of ropivacaine 0.5% was administered by mistake instead of the planned 40ml while performing interscalene block with a neurostimulator. Both studies report that adrenaline or dexamethasone as an adjunct to local anesthetic could prolong block duration. Dexamethasone also reduces nausea and vomiting (12).

The findings in these studies are consistent with our referred case, in which the patient was administered a total of 30ml local anesthetic (0.5% bupivacaine 20ml, 2% lidocaine 9ml and dexasone 4mg) for supraclavicular brachial plexus block as a stand-alone anesthetic technique. The patient had no side effects, no transient Horner’s syndrome or dizziness at the peak anesthetic absorption that occurs after 30 – 45 minutes.

Peripheral nerve blocks are of significant interest not only for anesthesiologists, but also for surgeons, considering the benefit to the patient, especially good pain relief and thus patient’s satisfaction with the type of anesthesia and surgical intervention, as well as the possibility of early discharge from the hospital. Some studies referred performing supraclavicular block by the orthopedic surgeons themselves in 20 patients undergoing upper limb orthopedic surgery. The time required to perform the block, the duration of the surgical procedure, and the duration of the block itself, which lasted an average of 7 hours, were measured. All patients experienced transient Horner’s syndrome immediately after the block, but there were no other complications or side effects. 97% of the patients were satisfied with the type of anesthesia (14).

Bilateral use of peripheral nerve blocks is controversial. Holborow et al., in their study investigated the possibility of performing a bilateral brachial plexus block for bilateral upper limb surgery. Bilateral blocks represent a great challenge, although traditionally they have been avoided by anesthesiologists due to concerns about systemic toxicity from the local anesthetic, phrenic nerve block and pneumothorax. Research of Medline and EMBASE, from 1966 to January 2009, was conducted using multiple search terms to identify techniques of providing anesthesia or analgesia for bilateral upper limb surgery and potential side effects. The use of ultrasound and catheter techniques for continuous analgesia also reduce the risk of local anesthetic toxicity, as does performing the block at different times which allows avoiding local anesthetic simultaneous peak absorption. Regional anesthesia has been shown to be beneficial for bilateral upper limb surgery but only as a continuous technique, except for interscalene brachial plexus block, due to the risk of phrenic nerve block, even with low doses of anesthetic (15).

In the case referred above, the supraclavicular block was performed in a conscious patient, previously sedated with diazepam 5mg. Peripheral nerve block performed in a deeply sedated or already anesthetized patient is still controversial. The conscious patient may cooperate and complain of severe pain during the application of the anesthetic, which is very important if the needle is not in the right place. However, peripheral blocks in children and sometimes in adult patients must be performed under anesthesia or deep sedation. The recommendations of Bernards et al., for the safe and effective performance of these blocks, are the introduction of ultrasound guidance, new modes of electrical nerve stimulation, and injection pressure monitoring (22).

Of course, peripheral nerve blocks are particularly suitable and safe for outpatient interventions such as shoulder and knee arthroscopy, hand contractures and other short interventions. Klein et al. in 2005 determined that the use of peripheral nerve blocks for outpatient interventions provides patients with excellent postoperative analgesia, a short stay and discharge from the hospital the next day, which reduces financial costs for both patients and hospitals. This increases not only the satisfaction of patients, but also of the surgeons themselves (19).

Among the listed contraindications for performing a peripheral nerve block is neuromuscular weakness. However, peripheral blocks were performed in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, which is a hereditary peripheral neuropathy characterized by progressive peripheral muscle atrophy and muscle-sensory impairment, especially in the extremities. There is concern about the application of peripheral nerve blocks, which could be associated with peripheral nerve denervation. It has been thought that peripheral nerve blocks could worsen pre-existing nerve deficits. Three studies have demonstrated the safe and successfully performed continuous or sole distal sciatic nerve block for foot surgery combined with epidural or spinal anesthesia (24-26). In all three subjects, local anesthetic was successfully applied through the placed catheter or through the needle without complications and worsening of the previously determined neurological deficit (24-26).

Single-injection regional blocks and continuous peripheral catheters play a valuable role in a multimodal approach to pain management in peri and post-operative period in all patients, especially in those with comorbidities, providing excellent patients’ comfort while reducing the physiologic stress response (5,6,10). However, compared to neuraxial and general anesthesia, success with peripheral nerve blocks is undoubtedly more anesthesiologist-dependent. Technical skills and determination are required for the successful implementation of peripheral nerve blocks. Factors such as accurate identification of surface landmarks and an adequate number of supervised, successful attempts at each block are necessary for safe and effective peripheral nerve block implementation (21).

Conclusion

When managing patients with compromised cardiovascular function, anesthesiologists need to select an appropriate anesthesia technique and carefully monitor vital signs to maintain hemodynamic stability during the perioperative period. Pulmonary and cardiac preoperative comorbidity, especially if previously untreated, represents a high risk for peri- and postoperative complications. Peripheral nerve block, in our case supraclavicular brachial plexus block, provides excellent anesthesia, maintains hemodynamic stability during the perioperative period, excellent postoperative pain relief, reduced postoperative complications and facilitates early physical activity and early hospital discharge in patients for upper limb surgery.

References

- Auerbach A. Goldman L. Assessing and Reducing the Cardiac Risk of Noncardiac Surgery. Circulation 2006; 113: 1361-1376.

- Fleisher LA. Beckman JA. Brown KA. et al. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Care for Noncardiac Surgery: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise theе 2002 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography. American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. Heart Rhythm Society. Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50:1707-32.

- Franklin B. A. et al. Using Metabolic Equivalents in Clinical Practice. Am J Cardiol. 2018. PMID:29229271 Review.

- Kim NY, Lee KY, Bai SJ, et al. Comparison of the effects of remifentanil-based general anesthesia and popliteal nerve block on postoperative pain and hemodynamic stability in diabetic patients undergoing distal foot amputation: A retrospective observational study. Medicine (Baltimore)2016; 95: e4302.

- Mallavaram N., Thys D. M. NYSORA Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. Chapter 57. Regional Anesthesia & Cardiovascular Disease.

- Ryan S. D’Souza, Rebecca L. Johnson. Supraclavicular block. National Library of Medicine Last Update: July 25, 2023; ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519056/

- Cornish P.B., Leaper C.J., Nelson G., Anstis F., McQuillan C., Stienstra R. Avoidance of phrenic nerve paresis during continuous supraclavicular regional anesthesia. Anaesthesia2007; 62: 354–358.

- D. Kaye et al. (eds.), Essentials of Regional Anesthesia 2012; DOI 10: 349-352.

- Soraes L., G. et al. Eight Ball, Corner Poccket: The Optima Needle Position For Ultrasound-Guided Supraclavicular Block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2007; PMID: vol32 No1.

- Neal JM. Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia and Patient Safety: Update of an Evidence-Based Analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016 Mar-Apr; 41(2):195-204.

- Kim, H.; Han, J.U.; Lee, W.; et al. Effects of local anesthetic volume (standard versus low) on incidence of hemidiaphragmatic paralysis and analgesic quality for ultrasound-guided superior trunk block after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Analg2021, 133, 1303–1310.

- Mardirosoff C., Dumont L. Convulsions after the administration of high dose ropivacaine following an interscalenic block. Can J Anaesth2000; 47: 1263.

- Koscielniak-Nielsen Z.J. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve blocks: what are the benefits? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand2008; 52: 727–737.

- Gamo K., Higuchi H. et al. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block in upper limb surgery outcomes and patient satisfaction. Bone Joint J2014;96-B:795–9.

- Holborow J. and Hocking G. Regional Anaesthesia for Bilateral Upper Limb Surgery: A Review of Challenges and Solutions. Sage Journals 2010; Volume 38, Issue 2.

- Lee B. H., Qiao W. P., McCracken S., Singleton M. N. and Goman M. Regional Anesthesia Techniques for Shoulder Surgery in High-Risk Pulmonary Patients. Clin. Med.2023; 12(10), 3483.

- Ozen V. Ultrasound-guided, combined application of selective supraclavicular nerve and low-dose interscalene brachial plexus block in a high-risk patient. Hippokratia 2019; 23(1): 25-27.

- Karm MH, Lee S, Yoon SH, et al. A case report: the use of ultrasound guided peripheral nerve block during above knee amputation in a severely cardiovascular compromised patient who required continuous anticoagulation. Medicine (Baltimore)2018; 97: e9374.

- Klein SM, Evans H, Nielsen KC, et al. Peripheral nerve block techniques for ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg2005; 101: 1663–1676.

- Lai HY, Foo LL, Lim SM, et al. The hemodynamic and pain impact of peripheral nerve block versus spinal anesthesia in diabetic patients undergoing diabetic foot surgery. Clin Auton Res2020; 30: 53–60.

- Roden E, Walder B. Preoperative evaluation and preparation by anaesthesiologists only, please! Eur J Anaesthesiol2013; 30: 731–733.

- Bernards C.M., Hadzic A., Suresh S., Neal J.M. Regional anesthesia in anesthetized or heavily sedated patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med2008; 33: 449–460.

- Dhir S., Singh S., Parkin J., Hannouche F., Richards R.S. Multiple finger joint replacement and continuous physiotherapy using ultrasound guided, bilateral infraclavicular catheters for continuous bilateral upper extremity analgesia. Can J Anaesth2008; 55: 880–881.

- Dhir S., Balasubramanian S. and Ross D. “Ultrasound- Guided Peripheral Regional Blockade in Patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Review of Three Cases,” Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, Vol. 55, No. 8, 2008, pp. 515-520.

- Bosenberg A. and Larkin K. “Anaesthesia and Charcot- Marie-Tooth Disease,” Southern African Journal of An- aesthesia & Analgesia, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2006, pp. 131-133.

- Schmitt HJ, Huberth S, Huber H, Munster T. Catherter-based distal sciatic nerve block in patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. BMC Anesth. 2014; 14: 8.