UDK: 616.24-085.816.2:616.123

Naumovski F1, Shosholcheva M2, Kuzmanovska B1, Kartalov A1, Jovanovski-Srceva M1, Trposka A1

1 University Clinic for Traumatology, Orthopedics, Anesthesiology, Reanimation, Intensive Care and Emergency Department – Skopje, Department of Anesthesiology, Reanimation and Intensive Care, “Ss. Cyril and Methodius” University – Skopje.

2 University Clinic of Surgical Diseases “St. Naum Ohridski” – Skopje, Department of Anesthesia and Intensive Care – Skopje.

Abstract

Even in terms of using lung protective strategies, mechanical ventilation could lead to different types of lung injury with severe consequences over systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics, showing deleterious properties over the right ventricular performance as well. Fifty polytraumatized patients admitted in the ICU were included in this prospective study. They were divided into two groups regarding the need for mechanical ventilation. In all patients we have examined Right heart function by measuring Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE) and Fractional Area Change (FAC) 24 hours, 7 and 14 days after admission in the ICU. Statistical analysis was done with calculating the mean value of TAPSE and FAC, as well as with using Mann Whitney U Test. In both groups, mechanically ventilated and spontaneously breathing patients, values for TAPSE were not significantly different at all examination points. The values for FAC were significantly lower in the group of mechanically ventilated patients after 7 and 14 days of mechanical ventilation initiation (U=275; 163,5; 86,5 and z= 0,7; 2,02; 1,96 for p value of 0,47; 0,04 and 0,04 respectively). TAPSE as a surrogate for the assessment of longitudinal systolic function of the right ventricle, has been intact in both groups regardless the usage of mechanical ventilation, but radial systolic function of the right ventricle was significantly lower 7 and 14 days after starting mechanical ventilation. Impairment of the radial systolic function of the right ventricle with preserved longitudinal systolic function was previously reported in patients with high pulmonary pressures and elevated right ventricular afterload. The mechanical ventilation is associated with radial right ventricular systolic dysfunction and with lower values for FAC in mechanically ventilated compared to spontaneously breathing polytraumatized patients.

Key Words: Fractional Area Change; Right Ventricular Systolic Function; TAPSE.

Introduction

Many life-threatening conditions demand mechanical ventilation characterized by Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) changing the normal physiology in order to achieve better gas exchange. Application of PEEP implies changes in the respiratory pressures that inevitably will have an impact over the pulmonary circulation altering right ventricular preload, afterload and finally right ventricular performance and function (1). It is already well known that applying PEEP could possibly alleviate left ventricular performance in patients with cardiac compromise but also can worsen right ventricular function. Spontaneous breathing generates negative pleural pressure at the end of inspiration associated with greater right ventricular preload and better right ventricular perfusion, in contrast, positive pressure ventilation implies creating greater right ventricular afterload due to positive pressure ventilation (2). The positive pressure ventilation by itself could lead to alveolar overdistension resulting in alveolar vessels compression while creating greater pulmonary vascular resistance, which implies elevation of right ventricular afterload. The elevation of right ventricular afterload has well known deleterious effects over the right sided myocardium with possibility of right ventricular disfunction development.

Aim of the Study

According to the above-discussed effects of positive pressure ventilation, right ventricular performance and function in polytraumatized patients demanding mechanical ventilation, will be examined and compared to spontaneously breathing patients not needing mechanical ventilation. The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of positive pressure ventilation over the right ventricle and to explore possible existence of association of mechanical ventilation with right ventricular dysfunction. Conduction of this study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Human Research of Medical Faculty – Skopje at “Ss. Cyril and Methodius” University – Skopje on 1st of February 2023 with number of approval 03-300/3.

Material and Methods

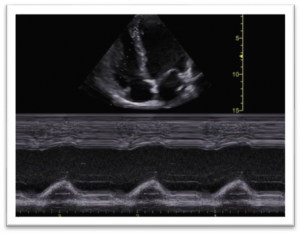

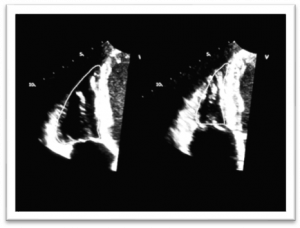

In this study we have included 50 patients admitted to the Department of Anesthesia, Reanimation and Intensive Care at the University Clinic for Traumatology, Orthopedics, Anesthesia, Reanimation, Intensive Care and Emergency Department in Skopje. All patients included in the study were polytraumatized adults with more than 18 years of age and had signed informed consent by their family member, since some of the admitted patients were unconscious. All patients that have not fulfilled the criteria for having polytrauma, patients younger than 18 years of age, pregnant women and already resuscitated patients, as well as those whose families did not provide informed consent for participation have not been included in the study. Regarding the need for mechanical ventilation, all patients included in the study were divided into two groups, a group of mechanically ventilated patients and spontaneously breathing patients not needing mechanical ventilation. We performed an echocardiography exam focusing on the right heart function in all patients that have fulfilled the inclusion criteria in three time points. The first echocardiographic examination was performed 24 hours after ICU admission, second exam was performed on day 7 of admission, while the third examination was done 14 days after admission. Right ventricular function was examined with measuring Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion (TAPSE) and Right Ventricular Fractional Area Change (RV FAC). TAPSE is a surrogate for assessment of longitudinal systolic function of the right sided myocardium, while FAC is representing radial systolic function (3). According to the European Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification in Adults, values for TAPSE and RV-FAC were measured in 4 chambers apical view of the heart (3). TAPSE was measured using M-mode echocardiography (Figure No.1A) referring to the systolic longitudinal displacement of the lateral tricuspid annulus towards the apex, since the septal annulus movements are relatively limited, and its value represents longitudinal systolic function of the right ventricle (4). Values for TAPSE less than 17mm were considered as systolic dysfunction (3,4). RV-FAC was measured in four chambers view with measuring Right Ventricular End Diastolic Area (RVEDA) at the end diastole and Right Ventricular End Systolic Area (RVESA) during the systole (Figure No.1B). RVEDA and RVESA values were used to calculate RV-FAC according to the following equitation: RVEDA-RVESA/RVEDA x100 (3). RV-FAC values lower than 35% were considered as a sign for radial right ventricular systolic dysfunction. Statistical analysis was done with calculating the mean value of TAPSE and FAC, as well as with using Mann Whitney U Test.

A |

B |

Figure 1. (A) M-mode measurement of TAPSE in four chamber view and (B) measurement of RVEDA and RVESA in order to calculate RV FAC.

Results

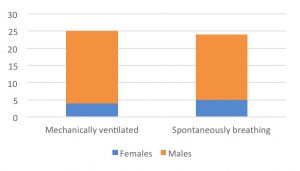

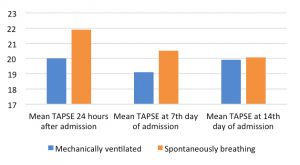

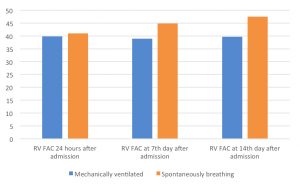

In total, 50 polytraumatized patients were included in the study where 26 of them (52%) were mechanically ventilated, while 24 (48%) were in the spontaneously breathing patients’ group not needing mechanical ventilation. In the group of mechanically ventilated patients 80.7% were males in comparison to the group of spontaneously breathing patients, where 79.1% were males without statistically significant difference in between groups (Chart No.1). Regarding the longitudinal systolic function, mean values for TAPSE were 20, 19.1 and 19.9 in mechanically ventilated patients 24 hours, on the 7th day and at the 14th day of admission respectively in comparison to 21.9, 20.57 and 20.08 in spontaneously breathing patients at the same examination points (Chart 2). Nevertheless, that at all measuring points the values for TAPSE were higher in the spontaneously breathing patients when compared to mechanically ventilated patients, using Mann-Whitney U Test, we did not found statistically significant difference in between both groups (p 0.07; p 0.123 and p 0.77) 24 hours after admission, on 7th day and on 14th day after admission in the ICU (Table 1). Mean values for RV-FAC 24 hours after admission were 39.8 in mechanically ventilated patients versus 41 in spontaneously breathing patients without any statistically significant difference between both groups (Mann-Whitney U test: p 0.47). On 7th day and on day 14 after admission in the ICU, the mean values for FAC were 38.9 and 39.6 in mechanically ventilated patients, respectively, versus 44.9 and 47.5 measured in spontaneously breathing patients, confirming that RV-FAC was significantly lower in the group of patients demanding mechanical ventilation (Mann-Whitney U test: p 0.04 and p 0.03) (Table 2 and Chart 3).

Table1. Mann-Whitney U Test values for TAPSE in mechanically ventilated versus spontaneously breathing patients.

| Mann-Whitney U Test | TAPSE 24 hours after admission | TAPSE on 7th day | TAPSE on 14th day |

| U | 216 | 184.5 | 161 |

| Z | -1.79 | 1.5 | -0.28 |

| p | 0.07 | 0.123 | 0.77 |

Chart 1. Distribution of patients by number and gender in both study groups: mechanically ventilated versus spontaneously breathing.

Chart 2. Mean values for TAPSE in both groups measured 24 hours after admission, 7 days after admission and 14 days after admission.

Table 2. Mann-Whitney U Test values for RV FAC in mechanically ventilated versus spontaneously breathing patients.

| Mann-Whitney U Test | RV FAC 24 hours after admission | RV FAC on 7th day | RV FAC on 14th day |

| U | 275 | 163.5 | 99.5 |

| Z | -0.7 | 2.02 | -2.1 |

| P | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

Chart 3. Mean values for RV FAC in mechanically ventilated patients versus spontaneously breathing patients 24 hours after admission, 7 days and 14 days after admission.

Discussion

Among all patients included in the study we could not found any gender related association with mechanical ventilation since regardless the need of respiratory support, the male to female ratio were similar in both groups where around 20% of polytraumatized patients were female. Similar results were found in the retrospective study of Weihs V. et al., where among 980 polytraumatized patients 30% were females which is confirmative that polytrauma in general is related with male gender, as presented in our results. Another study confirms the finding that polytrauma is more frequently met in males (5,6). Regarding the gender representation among polytraumatized patients with chest trauma, Jayle CP et al. found exactly the same male to female ratio where only 20% of patients experiencing flail chest were females, which is in accordance to our results (7).

Right ventricular disfunction (RVD) has been observed in severely injured patients and has been related to higher mortality, especially when it was found to happen in the early stages of polytrauma (8). Therefore, we have examined right ventricular performance and function with measurement of TAPSE and RV FAC as surrogates of longitudinal and radial systolic function of the right ventricle in mechanically ventilated, versus spontaneously breathing polytraumatized patients. Until now, TAPSE was considered as a “gold standard” in detection of right ventricular dysfunction and lower than normal values have been associated with bad outcome in mechanically ventilated patients (9). TAPSE lower than 17mm was considered as a cut off value for diagnosis of Right Ventricular Dysfunction (3). Since TAPSE is marker for longitudinal systolic function, we measured RV-FAC as a marker of radial systolic function. In our study, values for RV-FAC lower than 35% were considered as evidence for RVD existence which has been previously already stated and widely accepted (3,9). In the study of Simmons J. et al., TAPSE and RV-FAC were used to detect the right ventricular dysfunction in patients exhibiting respiratory failure and needing mechanical ventilation while in our study we use them to examine the effect of mechanical ventilation over the right ventricle in polytraumatized patients and its association with RVD, dividing the patients into two groups regarding the need for mechanical ventilation. Usage of mechanical ventilation was previously recognized as potentially hazardous for right ventricular performance and was considered as a risk factor for dysfunction development (10). Regardless of the previously discussed statement by Paternot A. et al. that mechanical ventilation could worsen the right ventricular systolic function, thus, when using TAPSE as a marker of longitudinal systolic dysfunction in our study, we found that mechanically ventilated patients exhibited lower values for TAPSE than spontaneously breathing patients, but those differences were not statistically significant in none of the examining points. Contrary, we have found that at all examining points mechanically ventilated patients have had lower values for RV-FAC which were significantly lower (p 0.04 and p 0.03) on the 7th day and 14th day of admission and commencement of mechanical ventilation. According to these findings, exposure of the patients to mechanical ventilation for at least 7 days leads to impairment of radial RV systolic function. Therefore, our findings confirm the existence of association between the usage of mechanical ventilation and de novo development of RVD in patients with previously intact right ventricle. The impact of positive pressure ventilation over the right ventricle and its relationship with RVD development was discussed and highlighted in the study of Oweis J. et al., where right ventricular function in COVID patients was examined using the same tools as we did in our study. Same as we found association of mechanical ventilation with RVD occurrence, they found positive correlation between usage of mechanical ventilation and existence of right ventricular dysfunction and/ or dilatation (11). Despite the same conclusion regarding the usage of mechanical ventilation and development of RVD, unlike in our study, in the study of Oweis J. et al., it was not specified which type of right ventricular systolic function was more affected, either longitudinal or radial. Positive pressure ventilation installation has been associated with worsening of right ventricular systolic function according to Magunia H. et al., where right ventricular function was examined with echocardiography in patients prior to and after positive pressure ventilation initiation (12). They found significantly lower values for TAPSE (p 0.0013) after initiation of positive pressure ventilation when compared to spontaneous ventilation in the same patients, suggesting that longitudinal systolic function could be altered in mechanically ventilated patients which was present in our study as well, because values for TAPSE were lower in the group of mechanically ventilated patients but still not statistically significant as in the study of Magunia H. et al. Nevertheless, we found significantly lower values for RV FAC in mechanically ventilated patients after 7 days of mechanical ventilation that have become even more significant after 14 days of mechanical ventilation, but that was not met in the study of Magunia H. et al. We believe that the difference between ours and theirs results could be explained by the difference in the study protocols, since they have assessed RV function in spontaneously breathing patients prior to induction in anesthesia and positive pressure ventilation initiation and immediately after that, while in our study those patients which were mechanically ventilated were sedated with continuous sedation not exhibiting strong effects over the hemodynamics as it does regular induction in anesthesia. Positive pressure ventilation initiation is related to increasement of the right ventricular afterload, while RV is extremely sensitive when changes in inspiration arise (13), therefore changes of function are more than expected especially in patients exposed to long lasting mechanical ventilation as it was seen in our study. Chu A. et al. recently have published a study where they evaluated the right ventricular performance in patients with obstructive sleep apnea that needed positive pressure ventilation in comparison to healthy subject group. Since in this study they have examined the effect of positive pressure ventilation over the RV, we consider that the results are worth and relevant to mention and compare to our results despite the differences in the study design. Therefore, they have found no significant differences in values for TAPSE, but significantly lower values for right ventricular end diastolic volume (RVEDV) and right ventricular end systolic volume (RVESV) were found in the group of patients that were exposed on mechanical ventilation (14). Those findings are in complete accordance with our findings, despite the fact that we were measuring RVEDA and RVESA instead of RVEDV and RVESV where both are surrogates for assessment of the radial right ventricular function. Obviously, in absence of significant difference in TAPSE found in our study as in the study of Chu A. et al. but detecting significantly lower values for RV FAC confirms that patients exposed to positive pressure ventilation are prone to suffer of right ventricular dysfunction where radial systolic function is affected, but longitudinal systolic function stays preserved even in terms of elevated right ventricular afterload. Lower values for RV FAC were associated with longer period of mechanical ventilation, which is confirmed in our study as well, since we met significantly lower values for RV FAC after 7 days of mechanical ventilation initiation which became even more significant after 14 days of mechanical ventilation commencement (15). We strongly believe that even more detailed analysis of the right ventricular function, as well as its morphology, could bring us even more useful data that could help in understanding the effect of mechanical ventilation over the right sided myocardium. We consider our results could serve as an initiator for further research on this topic where a greater group of patients will be assessed in order to provide even stronger conclusions. Modern echocardiography offers even more precise analysis of the right ventricle with use of Right Ventricle Speckle Tracking Echocardiography with right heart strain evaluation which could be helpful for further research. We mustmention that this study has its own limitations as well, since it is a single center study where a small sample size of patients were prospectively evaluated. The larger cohort of patients could be needed in order to provide more detailed results.

Conclusion

The usage of mechanical ventilation is associated with significantly lower RV FAC when compared to spontaneously breathing patients. Our findings imply association of radial right ventricular systolic dysfunction with positive pressure mechanical ventilation, while longitudinal right ventricular systolic function stays unaffected. Longer duration of mechanical ventilation has been related to worsening of already affected radial systolic function of the right ventricle.

References:

- Joseph A, Petit M, Vieillard-Baron A. Hemodynamic effects of positive end-expiratory pressure. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2024 Feb 1;30(1):10-19. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000001124. Epub 2023 Nov 29. PMID: 38085886.

- Alviar CL, Miller PE, McAreavey D, et al. ACC Critical Care Cardiology Working Group. Positive Pressure Ventilation in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Sep 25;72(13):1532-1553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.074. PMID: 30236315; PMCID: PMC11032173.

- Lang R, Badano L, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging, European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging, Volume 16, Issue 3, March 2015, Pages 233–271, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jev014 .

- Aloia E, Cameli M, D’Ascenzi F, Sciaccaluga C, Mondillo S. TAPSE: An old but useful tool in different diseases. Int J Cardiol. 2016 Dec 15;225:177-183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.009. Epub 2016 Oct 5. PMID: 27728861.

- Weihs V, Babeluk R, Negrin LL, Aldrian S, Hajdu S. Sex-Based Differences in Polytraumatized Patients between 1995 and 2020: Experiences from a Level I Trauma Center. J Clin Med. 2024 Oct 8;13(19):5998. doi: 10.3390/jcm13195998. PMID: 39408058; PMCID: PMC11478168.

- Joestl J, Lang NW, Kleiner A, Platzer P, Aldrian S. The Importance of Sex Differences on Outcome after Major Trauma: Clinical Outcome in Women Versus Men. J Clin Med. 2019 Aug 20;8(8):1263. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081263. PMID: 31434292; PMCID: PMC6722913.

- Jayle CP, Allain G, Ingrand P, et al. Flail chest in polytraumatized patients: surgical fixation using Stracos reduces ventilator time and hospital stay. Biomed Res Int. 2015; 2015:624723. doi: 10.1155/2015/624723. Epub 2015 Feb 1. PMID: 25710011; PMCID: PMC4331314.

- Eddy AC, Rice CL, Anardi DM. Right ventricular dysfunction in multiple trauma victims. Am J Surg. 1988 May;155(5):712-5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(88)80152-1. PMID: 3369631.

- Simmons J, Haines P, Extein J, Bashir Z, Aliotta J, Ventetuolo CE. Systolic Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography Is a Feasible and Sensitive Measure of Right Ventricular Dysfunction in Acute Respiratory Failure Patients on Mechanical Ventilation. Crit Care Explor. 2022 Jan 18;4(1):e0619. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000619. PMID: 35072083; PMCID: PMC8769114.

- Paternot A, Repessé X, Vieillard-Baron A. Rationale and Description of Right Ventricle-Protective Ventilation in ARDS. Respir Care. 2016 Oct;61(10):1391-6. doi: 10.4187/respcare.04943. Epub 2016 Aug 2. PMID: 27484108.

- Oweis J, Leamon A, Al-Tarbsheh AH, Goodspeed K, Khorolsky C, et al. Influence of right ventricular structure and function on hospital outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Heart Lung. 2023 Jan-Feb; 57:19-24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2022.08.007. Epub 2022 Aug 11. PMID: 35987113; PMCID: PMC9365873.

- Magunia H, Jordanow A, Keller M, Rosenberger P, Nowak-Machen M. The effects of anesthesia induction and positive pressure ventilation on right-ventricular function: an echocardiography-based prospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Nov 4;19(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12871-019-0870-z. PMID: 31684877; PMCID: PMC6829832.

- Repessé X, Charron C, Vieillard-Baron A. Assessment of the effects of inspiratory load on right ventricular function. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016 Jun;22(3):254-9. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000303. PMID: 27054626.

- Chu AA, Yu HM, Yang H, et al. Evaluation of right ventricular performance and impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea living at high altitude. Sci Rep. 2020 Nov 19;10(1):20186. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71584-9. PMID: 33214634; PMCID: PMC7678870.

- Younan D, Pigott DC, Gibson CB, Gullett JP, Zaky A. Right ventricular fractional area of change is predictive of ventilator support days in trauma and burn patients. Am J Surg. 2018 Jul;216(1):37-41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.02.002. Epub 2018 Feb 5. PMID: 29439775.